Land Sparing: The Miracle and Terror of Modern Ag

or, How a Nobel Peace Prize Winner Predicted We Were All Going to Die Without DDT

The Green Revolution, initiated by Norman Borlaug in the mid-20th century, was a transformative agricultural movement that dramatically increased global food production through the development of high-yield, disease-resistant crop varieties (particularly wheat and rice), combined with modern farming techniques, chemical fertilizers and biocides, and plastic-enabled irrigation methods.

Working primarily in Mexico and later expanding to India and Pakistan, Borlaug developed semi-dwarf wheat varieties and novel breeding techniques that allowed for two growing seasons per year, leading to dramatic increases in crop yields. This prevented mass famines in the developing world, and earned Borlaug the Nobel Peace Prize and the nickname "The Man Who Saved a Billion Lives."

One of the key enablers of the green revolution was the Haber-Bosch process. Developed in the early 1900s by Fritz Haber and Carl Bosch, the possibility of deriving synthetic nitrogen fertilizer from the atmosphere was a game changer. As Borlaug's high-yield crop varieties required significantly more nitrogen than traditional varieties to achieve their full productive potential, synthetic nitrogen fertilizers were a prime inabler of the green revolution.

Without on-demand availability of affordable nitrogen fertilizer made possible by the Haber-Bosch process, the Green Revolution’s dramatic yield increases would have been impossible. The new dwarf wheat and rice varieties were specifically bred to respond well to higher levels of fertilizer input without falling over. This created an agricultural feedback loop - the availability of synthetic fertilizer enabled the development and widespread adoption of high-yield varieties, which in turn drove even greater demand for fertilizer.

The last 80 years of agriculture have shown advances as significant as the discovery of irrigation in the Tigris-Euphrates 8000 years ago, animal domestication 6000 years ago, the steel plow, or the cotton gin. For lack of a better term, we can call this “chemistry-based ag”, in which synthetic fertilizers, the development of biocides, the possibilities of genetic engineering, and the dominance of fossil fuels and plastics, has enabled the human population to grow from 3 billion in 1960 to over 8 billion today.

At the same time, the % of population facing famine and hunger has dropped dramatically. MDG Monitor, which tracks progress on the millenium development goals, states that 780 million people today face undernourishment, representing a 50% drop in the global percentage of people facing hunger: from 23.3% facing hunger in 1990 to 12.9% today. It is a major triumph of humanity that we have enabled our populations to grow so large, and to have so few face hunger, and this is the miracle of modern ag.

Check the graphs below (all from Our World in Data) on how we have increased production of staple crops between 400 & 600% since the advent of the Green Revolution. The final graph shows our species’ total usage of land on earth to do so.

What these graphs tell us, is that by the most conventional and cited metric, that being production per acre, the green revolution has been nothing less than a marvel of human ingenuity. Total land use for arable agriculture has increased by 1.2 percent of total land, or increased by 11% overall, while productivity per acre has increased between 400 & 600%.

There is a tangent I need to bring in here, which is the narrative around population and food. “ We need to increase food production to feed a growing population” is a fallacy that puts the cart before the horse, because populations cannot grow beyond what food supply enables.

Consider the relationship of hares and foxes: when fox populations are low, hare populations skyrocket, enabling fox populations to grow, shrinking hare populations, causing fox populations to plummet. What would this look like if there were no predators to the hare? Would hare populations grow exponentially? No! They would strip all the foliage, until they eat everything, and then their populations would plummet, followed by a recovery of foliage, followed by a recovery of hares, followed by a drop in foliage, followed by a drop in hare populations. Species demography are closely related, and while humans may seem immune to this pattern, we really just have a massive lag time.

Everyone who says “ we need to grow more food to support a growing population” has it backwards. More food is what enables populations to grow in the first place. This may come across as nitpicky, but this is a critical dynamic in understanding one of the key weaknesses in the land-sparing narrative. Put that on the shelf for now, though.

One of Borlaug’s key contentions was that increasing agricultural efficiency would reduce land use for agriculture, and that it would enable us as a species to spare land for nature and biodiversity. As we see in the graphs above, the opposite is true: Despite massive increases in efficiency we have increased total land used for agriculture. The sparing argument falls apart here, because despite enormous increases in efficient use of land, we aren’t using less of it. We’re using more.

There’s no better example of Jevon’s Paradox in the ag world, than the USA and corn ethanol subsidies. Corn has become so efficient and so cheap that a full 40% of the USA’s corn crop isn’t even grown for food, but for biofuels, amounting to some 36 million acres:

Thus we see that efficiency, on its own, is not a solution to the question of how do we feed the world without destroying the earth. Efficiency means more food per acre, yes, but it also means higher profitability, cheaper prices, and thus higher demand for land and greater substitutability, leading to more land in agricultural use. per-unit efficiency is great, but it doesn’t spare anything, at least on its own.

Conversely, in some ways we are producing food much less efficiently. What about other metrics? What if land isn’t the limiting resource?

I started this post with Norm Borlaug, and I end it with him as well.

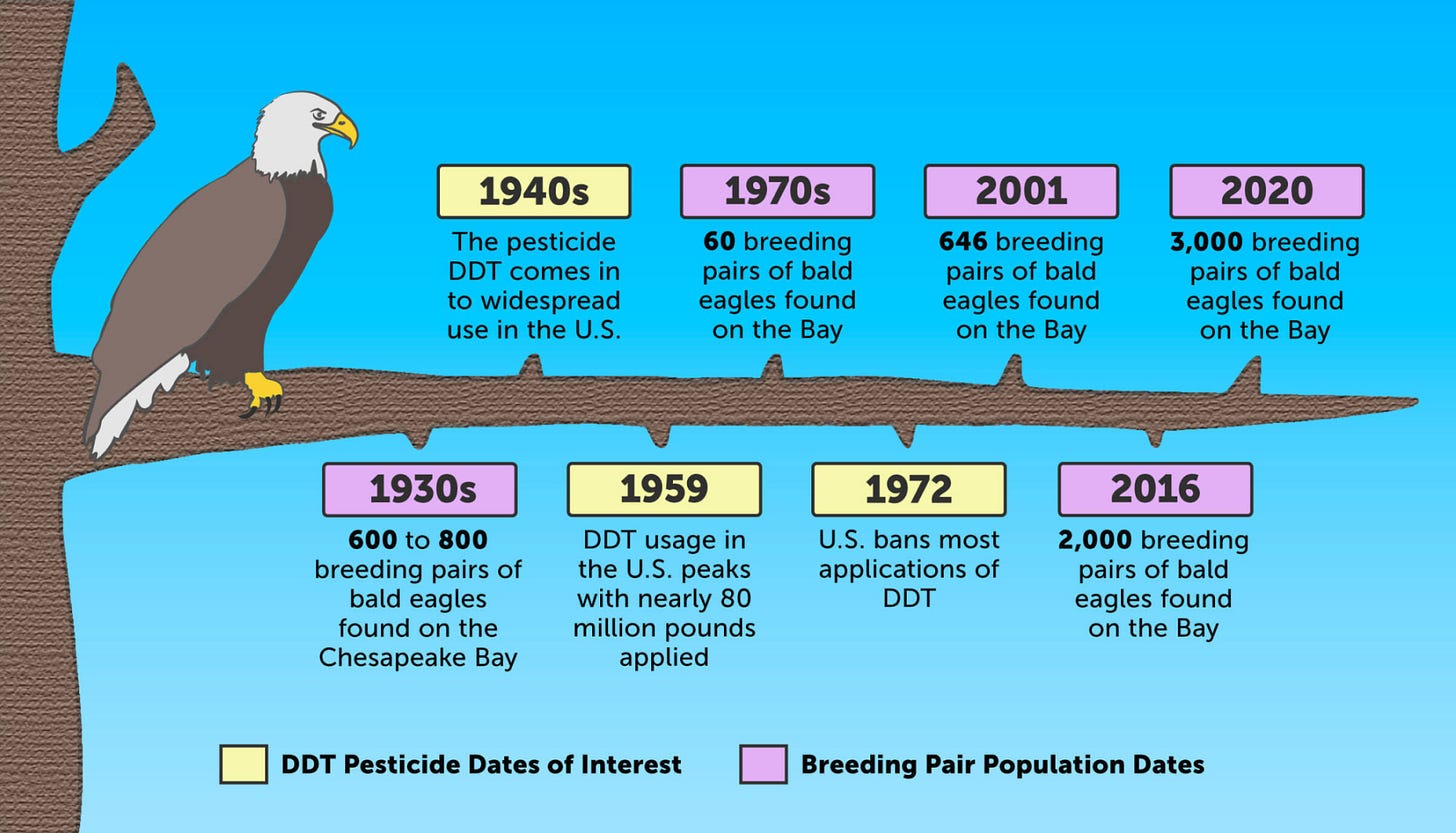

DDT was widely used in agriculture from the 1940s to the early 1970s. It was super effective, and super cheap. Its long-lasting effects reduced the need for frequent reapplication, and it helped control malaria through killing mosquitos.

DDT is so safe you can eat it!

Rachel Carson's 1962 book "Silent Spring" played a crucial role in raising public awareness about serious concerns about DDT. The chemical persisted for years in water and soil, without breaking down, and accumulated in the food chain. One of the most dramatic effects was the thinning of bird eggshells, which threatened bald eagles and peregrine falcons with extinction.

Scientists discovered DDT could build up in human fatty tissues and potentially affect child development. The presence of DDT in breast milk became a particular concern for public health experts. Evidence emerged linking DDT exposure to cancer and other health issues. It was banned in 1972 in the USA, and today it is used on a very limited basis for malaria control (I once got unknowingly sprayed with it in Saudi Arabia).

Norm Borlaug gave a speech to the FAO in Rome, defending DDT’s use, with words approximating the following: (*Note: this isn’t an actual quote, but I’m trying to recreate his narrative as closely to the sources as possible)

DDT has spared something like a billion people from the curse of malaria in the last quarter of a century, and allowed a healthier labor force to step up food production in tropical countries. Without this same hard pesticide, crop losses would probably soar to 50 per cent, and food prices would increase four to fivefold. No other pesticide is nearly so simple and cheap, and the environmentalists’ claim that DDT “causes cancer” is still wholly unproven.

https://www.nytimes.com/1971/11/26/archives/norman-borlaug-ddt.html

The so-called environmentalist movement is endemic to rich nations, where the most rabid crusaders tend to be well-fed urbanites who sample the delights of nature on weekend outings. Campaigns to ban agricultural chemicals—starting with DDT—reveal a callous misordering of social priorities. If such bans become law, he warned, “then the world will be doomed not by chemical poisoning but by starvation.”

https://time.com/archive/6839394/environment-whos-for-ddt/

Did crop losses soar to 50% after DDT was banned? Was the world doomed by starvation post 1971? Did food prices increase 4-5 fold? With 50 years of hindsight, it’s obvious that Borlaug’s argument was completely wrong. Food continued to get cheaper, productivity continued to increase, people developed a vaccine for malaria (we need a giant global celebration for this by the way), all without needing to drive birds of prey extinct. I for one am glad that we still have bald eagles.

Today, land-sparers, agribusiness PR clients, and plenty of farmers, love to talk about Sri Lanka’s famine and its catastrophic attempt at embracing organic agriculture, as if that is the only alternative to today’s food systems. Much like Borlaug, they believe only their way of growing food can feed the world, and denigrate the privileged and misanthropic elite who care about the environment more than about people. Borlaug’s speech on DDT is no different from assertions today that we need dicamba, or we need glyphosate, and if we get rid of these poisons we’ll all starve to death.

Just like Borlaug on DDT, all of that boils down to a false dichotomy. In what I can only describe as a profound irony, land-sparers echo Malthus, in that they fail to account for man’s ingenuity and creativity, and our ability to come up with better solutions, especially when those better solutions are incentivized.

Borlaug was right about a lot, and deserved that Nobel Peace Prize. Also, he was deeply mistaken that efficiency can only be gained through chemical means, or that it’s either (name your favorite ag chemical here) or starvation. And he was reportedly crestfallen when he learned that greater efficiency per unit of land leads to more land under use, not less. But he did feed a billion people, and that deserves to be celebrated.

Modern agriculture feeds us; we are not hungry in a way our species has never been in our history, and this is an absolute miracle. Beyond a miracle, it is a testament to what I believe is our species’ greatest advantage: creativity and adaptation. In my next post, i’ll talk about why that creativity and adaptation needs to be directed to solving the problems of the green revolution, as modern ag isn’t just a miracle. It’s also a terror.

It would be interesting to see a graph of the increased irrigation need to increase uptake of synthetic nitrogen (especially nitrates), since my understanding is that the green revolution also entailed a huge (unsustainable) increase in irrigation (200 to 250%) that made it possible to farm more marginal land and thus put a lot more acres into production.