When I was starting out in my study of ecology and its application, I found an affinity for using how we classify certain species and their role in ecosystem function, and applying those to people in social and economic settings. For instance, something that classifies as a pioneer species:

Is first to colonize disturbed or barren areas.

Is highly tolerant of harsh conditions (extreme temperatures, poor soil, etc.)

Typically have excellent dispersal abilities

Help create microclimates that allow other species to establish.

An example of a pioneer species are Lichens, which are a symbiosis of fungi and algae that can colonize bare rock, and become a catalyst for soil production and eventually ecological succession.

I think of some people the same way. Some people are like pioneer species — they can thrive where others can’t be at all, and they create all kinds of follow-on opportunities. At the same time, they may be prickly and metaphorically full of thorns, as that’s what allows them to get by in harsh conditions. Other people are edge species, or symbiotes, or parasites, or scavengers, etc. In learning how ecosystems function and the different roles different organisms play, i’ve come to put people in similar boxes and then expect them to behave in similar ways.

I’ve found this kind of analogy super useful. For instance, I once got in a fight with Allan Savory (on facebook!) over the relevance of holistic management / regenerative grazing in true deserts vs in degraded grasslands. During that discussion, I thought to myself, “I’m dealing with a person who is a pioneer species— he’s had to develop prickly spines to deal with all the naysayers and doubters — and he may see me as allelopathic rather than symbiotic.” And this helped me not take things personally and led to a much more productive discussion than it may have been otherwise.

I start with that vignette because knowledge of ecology has greatly influenced how I see individuals functioning in human society, but also because it’s led to some prolonged thought on how we interact with nature and what our real ecological role is. And I’m convinced that the dominant narrative we have today is both wrong and counterproductive. I call that dominant narrative the Agent Smith Narrative.

The Agent Smith Narrative:

The dominant narrative about people and the environment today is that we are inherently bad for earth. And if we are inherently bad for earth, then the very best thing we can hope to be is less bad. From this attitude stems the entire narrative around reducing our footprint and increasing efficiencies — efforts aimed at minimizing the damage we do. This narrative is everywhere — almost all “climate tech” companies use it, as do almost all food companies. Indeed, when they talk about the beneficial impact they have, it’s not about actually benefiting the earth, but on being less bad.

In the Matrix, there’s a monologue Agent Smith gives about where people fit in nature’s taxonomy:

I’d like to share a revelation that I’ve had during my time here. It came to me when I tried to classify your species and I realized that you’re not actually mammals. Every mammal on this planet instinctively develops a natural equilibrium with the surrounding environment but you humans do not. You move to an area and you multiply and multiply until every natural resource is consumed and the only way you can survive is to spread to another area. There is another organism on this planet that follows the same pattern.

Do you know what it is? A virus.

I’m under the impression that most people agree with Agent Smith that homo sapiens is like a virus. There’s a lot of evidence to back up the idea. Millenia ago, The first peoples of every continent (except for Africa) drove the megafauna of their regions extinct (In Africa it didn’t happen because the animals had enough time to adapt to humans as a predator). Today, from the great garbage patch in the Pacific, to dead zones in our oceans, widespread deforestation, desertification, and the 6th great extinction are all evidence of our species’ capacity to consume. Hence the misanthropy, the anxiety and guilt, and the hopelessness that can accompany the awareness of just how badly the human race has messed up this planet.

But there is a different type of taxonomy where species manipulate their environment so thoroughly that it changes whole landscapes: a keystone species. And in general, keystone species create landscapes in such a way that it benefits local ecosystems. Beavers, prairie dogs, sea otters, African elephants, wolves, gharials, and tigers, are all keystone species that maintain ecosystem health and function — directly manipulating water and mineral cycles by virtue of instinct and their activity in such a way that it benefits their surrounding ecosystem.

So here’s the question: Can humans act as a keystone species and develop resource management schemes that benefit biodiversity and that improve ecosystem function while caring for human needs?

Yes we can.

I’ve done it.

At the Al Baydha Project, I lived and worked with tribes of settled nomads, and together we did it. We started with a highly degraded watershed, one that had been denuded through wood-harvesting, overgrazing of camels and goats, and one of the most challenging climates on the planet, with less than 2 inches of rain a year on average, and going up to 30 months without any rain during my tenure there.

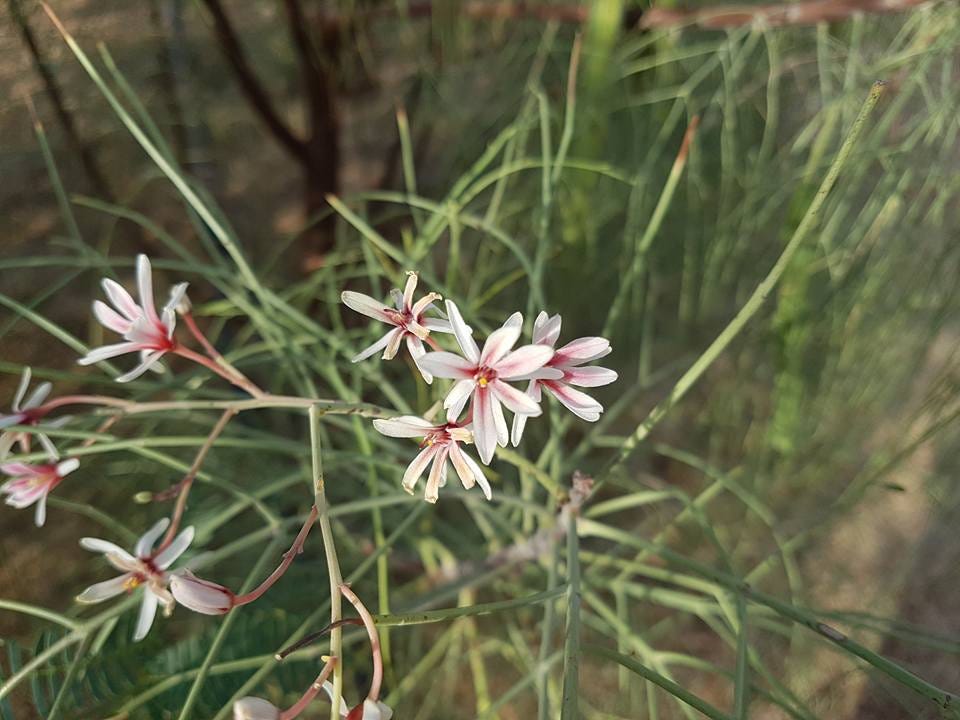

At Al Baydha we saw the entire trophic cascade come back, starting with mycellia, and then plants and insects, and then lizards and birds and snakes, and finally predators. Most of what we did was move rocks and dirt around to change how water interacted with the landscape, and we also planted trees to prototype an agroforestry. And at the same time, we saw the beginnings of soil creation, increased total water resources, and increased the carrying capacity of the land so that people could begin to graze it again. Thus, we prototyped a system to both reverse desertification and provide the foundational resource base for people to take care of themselves, primarily through increased grasses and through silvopasture.

Today, thousands of plants and animals live because of the work we did in Al Baydha. Satellite data shows the site getting greener every year, even with zero maintenance. I don’t know how to communicate the profoundsense of satisfaction that comes from this kind of work, but i imagine that it is almost like giving birth. We had a 9 year gestation period, and birthed an ecosystem. It is sublime to see wild bees swarm in a tree we planted. It is profoundly meaningful to see birds build nests on a landscape we brought back to life. We were the keystone species that resurrected that watershed, and the same can be done with much larger landscapes around the globe, managed to provide for both nature and people.

I wish you could experience what that’s like. It starts with knowing that such a thing is possible, and understanding that we are the keystone species, with the potential to manage land and water to maximize life and expand earth’s carrying capacity, while caring for ourselves. I end with something i wrote for the Al Baydha video:

We are not destructive by nature, but by habit. Our potential for destruction is mirrored by our potential for regeneration. If we recognize our true role as a keystone species, we can be the primary vector for restoring ecosystems and healing the earth.

~Neal

Beautiful story and a powerful metaphor. Humankind as a keystone species is what Kat Anderson described in Tending the Wild.” Thank you

Sorry to double comment, but if your interested at all,

https://natureliketechnology.substack.com/p/the-chicken-or-the-egg

https://natureliketechnology.substack.com/p/hope-on-the-horizon

These may make more sense to read, rather than a more poetic rambling about Mayan land use practices.