The last few posts on land sparing analyzed the argument that efficiency reduces impact and the feedback loops on intensive ag systems that make them long-term suicidal. The sharing side of the argument traditionally emphasizes less intense food producing systems that are friendlier to nature, but that inherently use up more land.

The roots of such an argument go back to some indigenous systems where people have maintained ecological function and health while providing for human needs. I have written elsewhere on some of my favorite indigenous systems, so this is a bit of a retread if you’ve been following me a few years. One of my other favorite indigenous systems (and there are so many!) is the Dehesa of Iberia.

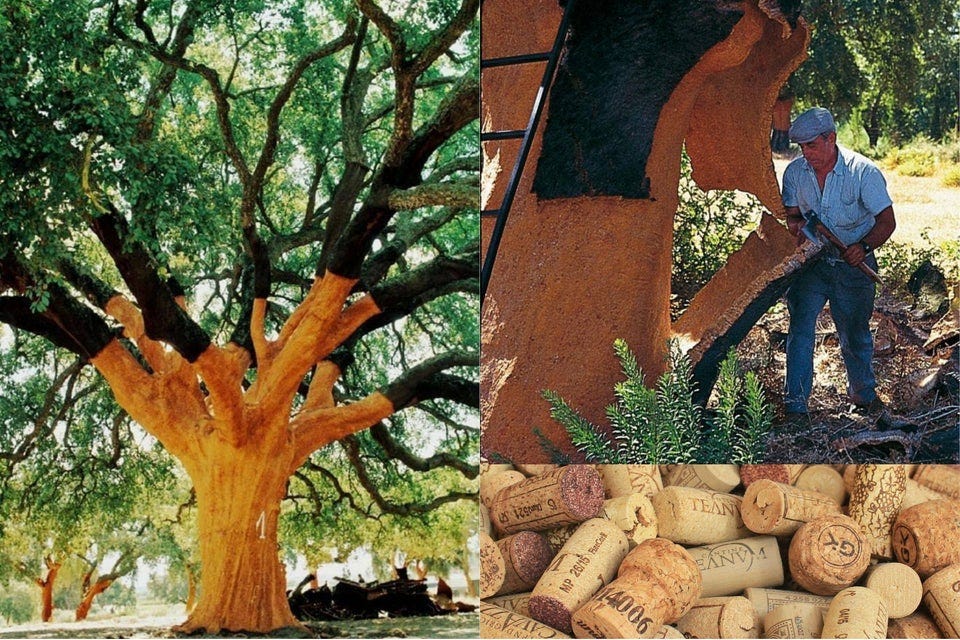

Based on the cork-oak (Quercus faginea) and pigs, the Dehesa (or Montado in Portuguese) is an indigenous silvopasture system that used cyclical harvesting of the oak’s bark, and the trees acorns as a primary feed for pigs. Cork has been used for millenia — the Egyptians, Greeks and Romans used cork to cover pots and jars and to make floats for fishing tackle. The Arabs used it as thermal insulation in their homes and the Chinese used it in shoes. Today most of the cork from Iberia is used to stopper up billions of wine bottles a year — but the material itself is incredibly versatile. The ham from a dehesa system is famous worldwide; with specially adapted pigs fattening on acorns, pata negra jamón iberico sells for between 40 and 100 USD per pound.

The Dehesa, in addition to being highly productive and infinitely sustainable, is also critical in preserving endangered wildlife in Spain and Portugal:

“Dehesa is vital to the continued existence of birds such as the Spanish imperial eagle, its world population only about 170 pairs; the black vulture, Europe’s largest bird of prey; and the rare black stork,” says Dehesa expert Mario Díaz, associate professor of zoology at Castilla La Mancha University in Spain. Wildcats, Iberian lynx and common genets — small, long-tailed, catlike mammals sacred to the ancient Egyptians — patrol the dehesa at night, hunting for smaller mammals and birds. A few packs of wolves and the occasional giant-sized eagle owl do the same. (from the National Wildlife Federation)

The Dehesa is an indigenous food system that, contrary to most dominant modes of agriculture today, maintains water, soil, & biodiversity. It does so by managing the land, functionally, as a savannah—based on oak trees that can produce for hundreds of years without irrigation, without pesticides, herbicides, or fungicides, and without the need for synthetic fertilizers, while maintaining large open spaces. How long can the Dehesa system last? Forever.

Contrast this with conventional modes of food production today, and the tradeoffs become very apparent — the dehesa does not suffer from the same suicidal trends as monocropping, in that it maintains or increases soil, water, and biodiversity, instead of degrading them. It can last forever, provide very high-quality foods, while producing fewer calories than a monocropped corn field in the short run. In the long run, a monocropped corn field’s productivity will go to zero, whereas a dehesa’s intecrated cork and pork system will remain stable.

There are numerous other indigenous systems we could highlight that follow the same pattern, though I want to note that not all indigenous systems follow these patterns, and not all indigenous food systems are sustainable. But many of them are, and they tend to hold true to the following:

1. They manage ecosystems as such, rather than converting them into wholly human landscapes. The Marsh Arabs of Iraq, the Uru of Lake Titicaca in Peru, and the Yang Tze Cormorant fishers represent drastically different peoples, languages, and culture, but all inhabit riparian wetlands, and manage them as such — they don’t drain the wetlands, divert the rivers, or deplete water sources for irrigation, but manage their food systems as intact ecosystems.

2. They manage integrated landscapes deriving multiple products and providing all their needs through polycultural systems, including housing, clothing food, and commerce. This utilizes ecological synergy.

3. They incorporate rules that maintain ecosystem function and prevent overharvesting—the Ahupua’a of the Pacific, for instance, ban any tree cutting above a certain elevation in order to maintain the cloud forests, the rainfall, and the small water cycle.

4. They maintain and replenish water, soil, and biodiversity, thus preserving the foundation of their livelihoods and food systems.

All that being said, just because a food system was indigenous doesn’t mean it was sustainable — there are plenty of examples of indigenous peoples who depleted their environment, and I don’t want to propagate the noble savage trope. But there are indigenous roots to the land sharing argument i want to lay the foundation with.

The next part of this series will go deep into the land sharing argument; as with land sparing there are significant strengths and weaknesses, but also commonly overlooked aspects that escape much of the conversation. After which, i’ll go into my own take on the sharing vs sparing argument, as well as real solutions that I believe point the way forward.