The False Promise of Blue Carbon

How I inadvertently became a carbon developer, and why I'm pivoting away from it in efforts to restore blue ecosystems.

I’ve been professionally involved in ecosystem restoration and regenerative development for a decade and a half. In the last six years, I've been involved in carbon projects in Latin America, West Africa, the Middle East, Europe, and Central Asia, from being the main project developer to being an advisor. Most of have been stymied at some point in the development schedule, for numerous reasons. They’ve spanned multiple ecosystems: mangroves, seagrasses, steppe, saltmarshes, desert forestry, and grasslands. I’ve designed for multi-ecosystem projects that ran from mountaintops all the way to coral reefs, covering hundreds of thousands of hectares.

None of these projects were strictly conservation. My passion and my skillset revolve around bringing dead places back to life, so I tend to work with highly degraded landscapes, rather than intact ecologies. In none of these projects were we pretending that an existing ecosystem was threatened in order to generate payments for a hypothetical counterfactual (REDD+ proponents may feel this is an unfair characterization; I don’t deny the benefits that have come in Redd+ contexts, but I’ve never liked the adverse incentives those structures create).

I've come to realize that harnessing carbon finance to restore degraded ecosystems is extremely limited in its application, extremely difficult to pull off, and for the majority of contexts, a non-starter. That’s because you need the perfect recipe of amenable national and local policy, agreeable land holders, aligned local communities, ecosystems that will sequester enough carbon to justify project costs, large enough scale, an experienced team that can execute the project successfully, a lot of cash up front, and some very good luck, and you need all of that without any external funding. Today each of these things is very hard to come by, but having all of them together means that the application of carbon crediting is limited at best, and nigh impossible in most circumstances and for most people. This is particularly true in a blue carbon setting.

A good example is one of the projects I helped lead as part of Regenerative Resources (a company I cofounded in 2019 with 5 partners and that is in the process of shutting down).

Project: DELGADITO

Delgadito is a fishing village in the Vizcaíno UNESCO biosphere, on the Pacific coast of Baja California Sur, Mexico. This lagoon is where Pacific Gray Whales come to calve, making it a nexus for the health of the eastern Pacific ocean.

Along this lagoon there are hundreds of fishing teams spread among a half dozen fishing communities. Fishing comprises the bulk of the local economy except for January and February, when there is whale tourism. Local reports say the catch is down 90% compared to 15 years ago, indicating a collapsing fishery, and the collapse of the traditional economy, putting enormous pressure on the people.

A complex set of factors is threatening these communities, though the pattern is one i’ve seen in coastal communities on three different continents. One is population growth and pressure on the fishery. Two is the degradation of sea grass and mangrove ecosystems, which contributes to the degradation of the fishery. The youth don't see real opportunities here anymore. They don't want to keep being fishermen, because they see that fishing is no longer really a viable option. And the tourism can't grow that much without threatening the source of tourism; the whales.

Five years ago, I was sitting at dinner in La Paz, Mexico, with my partner Christian Bertacchini, discussing projects in Baja that we were evaluating. Someone from the table next to us approached us and asked to assess the situation up in Laguna San Ignacio, and see if it wasn't a fit. That led to a number of community meetings where we met with the different villages, with the ejidos, with local government actors, as well as officials from Mexico’s relevant environmental ministries. One of the things the community asked us to do was support a mangrove restoration project. They had identified the restoration of mangroves as both a potential solution to part of the fishery problem, but also creating communal resilience. There's a recognition locally that their livelihoods depend on healthy ecosystems.

In that process, we met David Borbón, a fisherman by trade, who had switched to oyster farming. David and his wife Ana Murillo have planted over a million mangroves in their time and developed their own system for mangrove restoration in Baja. David’s trust did not come quickly, but eventually he understood our experience and our objectives and decided to collaborate with us. David’s reputation is growing, as he has since been profiled in Hakai Magazine and Mongabay.

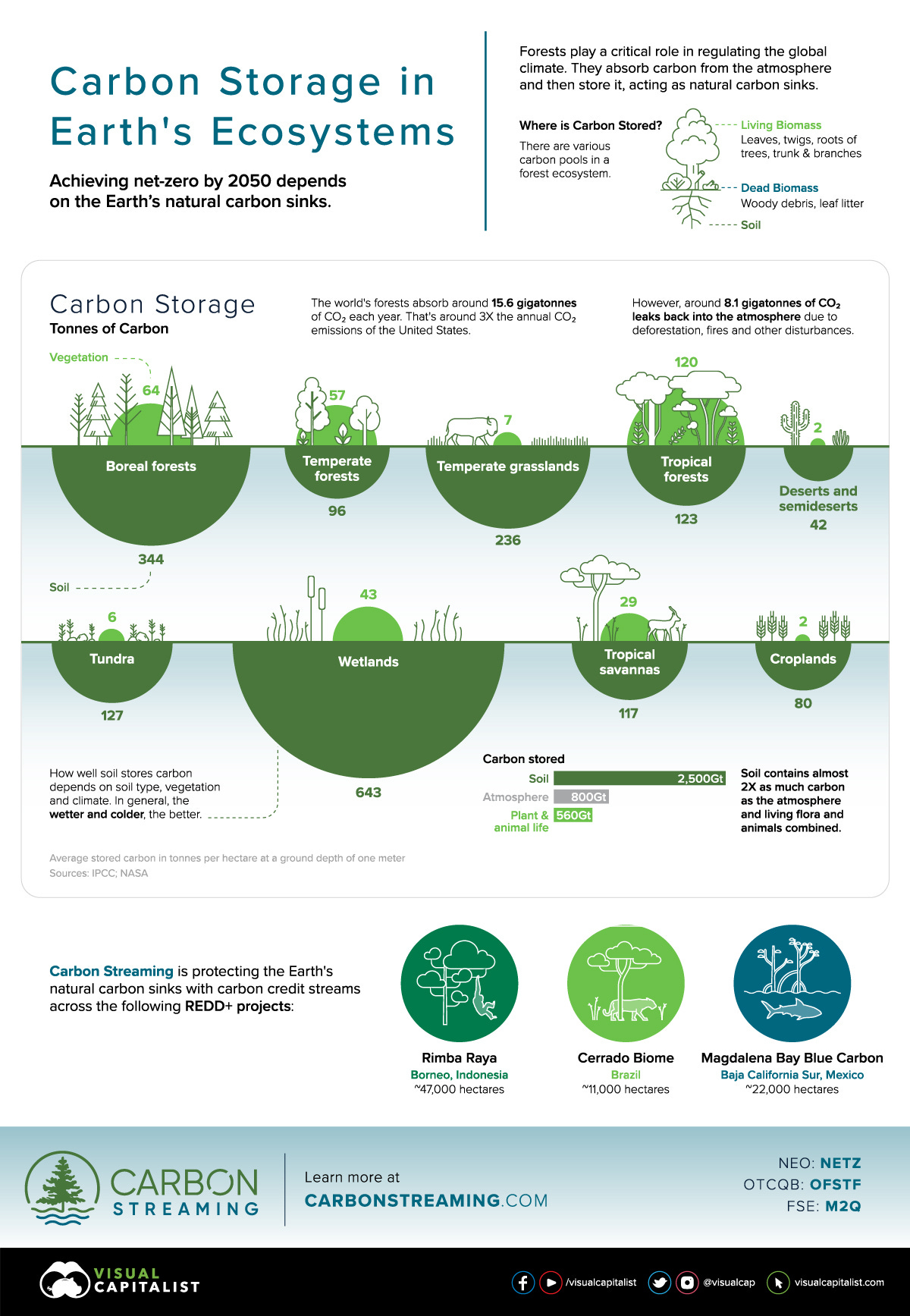

Up to that point, we had not considered blue carbon to be a key part of our work, but we knew the buzz around mangroves and blue carbon, and one of our partners, Ned Daugherty, had planted millions of mangroves in a variety of contexts over the course of his career. For some of that buzz, check the two graphics below which made the rounds a few times in climate / carbon circles.

Here’s another:

Thus we had key foundational aspects of a successful project in place, after approximately a year of community engagement and research:

1. The support and buy-in of local communities

2. Thousands of hectares of degraded mangroves needing restoration work, with some of the highest potential for carbon sequestration among all ecosystems!

3. An experienced team, combining decades of international work in blue ecosystems, ecosystem restoration processes in general, and local indigenous knowledge.

4. An ability to promise durability and permanence to our restoration work, given that it was already in a legal conservation setting.

5. Existing permits through our local partner to do restoration.

This was an opportunity to execute mangrove restoration at scale, hand in hand with local communities, at their request. We weren’t imposing ourselves, we weren’t engaging in neocolonialism, and we weren’t commandeering anything. Beyond that, we had regenerative aquacultures and seawater agroforestry systems we could bring in to help create local regenerative economies that would further foster rehabilitation of the blue ecosystems. It seemed a perfect fit.

We put together a project plan, and went after some grants to start. We got a couple grants from family offices and from Regen Network, which led to a grant from One Tree Planted. With those we were able to grow just over 500,000 mangroves across 50 hectares, while training a local team and establishing practices for seed collection, sorting, transport, planting, and maintenance. The vast majority of the funds we got was funneled to the work on the ground. Those of us in Regenerative Resources were hoping for other revenues to come in, or to get larger project funding based on the work we had already done.

We reached out to a number of carbon crediting platforms to keep ourselves going, offering to forward-sell credits to fund the rest of the predevelopment work (we were about 18 months into the process at this point). This was a no-go. Despite our accomplishments, and despite active ongoing restoration, nobody was willing to put significant funds into this beyond the philanthropy we’d pulled in. We learned we needed to register our project with a credible registry, needed the science and financial modeling on how much carbon we could expect to sequester, needed to write a Project Initiation Note and Project Design Document (PIN and PDD), and most importantly, legal permits to commercialize the carbon credits we were developing. Once we had all that done, then our project would be investable from a crediting standpoint.

Some of this we could do quite easily. Some of it turned out to be impossible, especially without any more funding. In the process of restoring that first 50 hectares, we hit two impenetrable barriers. First, even though the mangroves in the region sit on 4 meters of peat, representing enormous amounts of soil carbon per hectare, he rate of sequestration in these areas was too low to justify the cost of a restoration project. Mangroves in Laguna San Ignacio, we learned, will sequester between .5 and 1 ton of carbon per hectare per year, and we needed the sequestration rate to be 8 tons minimum for financial viability, and much preferably 15-20! Second, even though we had the permits to do mangrove restoration, because Mexico didn’t have a firm policy around carbon crediting on public lands, we couldn’t secure legal guarantee to the carbon for our buyers.

It was a kick in the teeth to realize that we wouldn't be able to use carbon to fund this important restoration work. We had done everything right, but the bad luck of incompatible geography, and a lack of relevant science when we started out, made it impossible. We did a quick assessment of the seagrass potential in Laguna San Ignacio — which is also significant in scale. But came to a similar conclusion: it costs way too much to restore seagrasses compared to the potential carbon revenues to make blue carbon a viable instrument for funding that restoration work.

I have since learned that this is true for the majority of mangrove and seagrass ecosystems globally. Based on reports i’ve seen, humans have eradicated around 50% of the world’s seagrasses and mangroves in the last century. They are critical for ocean health, planetary health, and for food. We know how to restore them, we know how important they are, but the scale of finance needed is massive. It is beyond what philanthropy can do, and beyond what public finance, in most cases, is willing to do. If the projects i’ve been part of the last 5 years were funded, we would be growing 200 million mangroves across tens of thousands of hectares in three different countries and creating regenerative economies to bolster fishing communities that today are facing collapse. But in most of the projects i’ve been on, it’s not possible. The rate of sequestration simply doesn’t justify the cost of restoration, and despite what folks in carbon markets may say about impact or cobenefits, really what the buyers care about is carbon. And the carbon’s not enough. I’ve verified this for multiple geographies, in multiple countries where mangroves are native, under threat, and highly degraded. Carbon financing won’t do it. There are exceptions! Shoutout to Steve Crooks and Vahid Fotuhi who are getting it done in some of the appropriate geographies — but my point is that these are exceptions, and not the rule!

I’ve only touched on the finance aspect of this, but it deserves a couple paragraphs. I have never felt more frustrated than when folks sitting on the corporate or investor side of these deals have told me how much money is available for blue carbon. It’s a smokescreen. Buyers and investors are waiting for project developers like myself to deliver unicorn projects on a silver platter— projects that can deliver a million tons per year, with all the political, financial, geographic, ecological, and local community risks tied up in a pretty bow. They have no idea how difficult and costly it is to put that kind of thing together, or they simply don’t care. They take no risk, despite having enormous amounts of capital at their disposal. The investors put money into platforms, or tech that supposedly enables restoration and carbon credit development, failing to recognize that all MRV and tech needs viable projects to deploy them. Bottom line: There is no money for projects until they are completely derisked. People say to me, “Don’t give up Neal, there’s so much money out there for this stuff.” They haven’t learned that the money out there isn’t for those of us taking the risk to put these projects together. Derisking everything is a process that takes lots of time and capital and skill. I’ve got time and skill, but i don’t have capital. And the folks with capital aren’t willing to share risk.

The second major financial challenge is everybody is trying to maximize their take. The pie’s getting split too many ways. I was part of a big project where the regulators wouldn’t approve anything without 30% of all the carbon going to the government, which blew up the whole plan. It was completely unfeasible, because we couldn’t get a return to investors with that much of the pie eaten up by the state.

Lots of people say philanthropy needs to step in to fill the predevelopment gap. In my experience, philanthropists want impact, not reports and permits and financial models that deliver derisked projects for Microsoft, Shell, and Totale .

I’ll give a couple anecdotes on this: an officer from a very well known financial institution gave me a call summer of 2024. This bank is a household name with billions of AUM and billions in annual profits. This officer called me and said, “Neal, we have clients who are really interested in blue bonds as a product — do you have anything like that?” I said, “No, but I could in 18 months if you’re willing to fund the work”.

“Oh no, we can’t do that.”

I had another call with a big carbon buyer — this buyer has billions in resources and a public commitment to carbon neutrality in 6 years, and a need for millions of carbon credits to reach that goal. I asked for funding to get a project across the line that I know could deliver very high quality credits at scale. “No, we take a year to do our due diligence, and you need to reach more milestones before we can consider going through that process.”

Well, I can’t reach more milestones. I’ve put in my widow’s mite trying to make this work, with half a million mangroves grown on 50 hectares, and a lot of hard learned lessons. Meanwhile, all these degraded ecologies where carbon is not a feasible vehicle for finance, need restoration. The loss of ecosystems is existential, but their value today is only measured in the carbon they sequester.

Bottom line: Carbon is not the answer we thought it was going to be. It’s applicable in very limited contexts where regional and local politics, geography, and finance align, which rules out most of the world’s blue ecosystems. It’s not enough to fund any seagrass restoration, as far as I can tell, and limited on mangroves. And mangroves and seagrasses are half of the ecosystems that make up “blue carbon”. Furthermore, until folks with resources are willing to share risk, folks like me with the skillset to make these projects happen aren’t going to be putting those skills to use. If multibillion dollar companies aren’t willing to take any risk in this, then why should I?

I’m still dedicated to finding a way to restore the mangroves and seagrasses in Delgadito, and in other projects i’m part of, where carbon crediting won’t fund the work. How we do that will be the subject of future posts.

Thanks for sharing your experiences, Neal. I'm so sad and infuriated for you and all your partners that the Delgadito project hasn't been able to find funding. I know how much you put into this - and if anyone could have made it work, you would have.

What makes me maddest is that the derisking involves so much trust-building with local stakeholders, and every time the money fails to arrive it erodes that trust, and makes it harder to ask for it when entering into the next projects.

I have so much respect for the work that you (and other skilled project developers) are doing - and look forward to hearing your thoughts on alternative approaches to this huge challenge. Hugs from the UK!

This is happening to hundreds of us around the world. You're the best of the best and if you can't do it then....

"I’ve only touched on the finance aspect of this, but it deserves a couple paragraphs. I have never felt more frustrated than when folks sitting on the corporate or investor side of these deals have told me how much money is available for blue carbon. It’s a smokescreen. Buyers and investors are waiting for project developers like myself to deliver unicorn projects on a silver platter— projects that can deliver a million tons per year, with all the political, financial, geographic, ecological, and local community risks tied up in a pretty bow. They have no idea how difficult and costly it is to put that kind of thing together, or they simply don’t care. They take no risk, despite having enormous amounts of capital at their disposal. The investors put money into platforms, or tech that supposedly enables restoration and carbon credit development, failing to recognize that all MRV and tech needs viable projects to deploy them. Bottom line: There is no money for projects until they are completely derisked. People say to me, “Don’t give up Neal, there’s so much money out there for this stuff.” They haven’t learned that the money out there isn’t for those of us taking the risk to put these projects together. Derisking everything is a process that takes lots of time and capital and skill. I’ve got time and skill, but i don’t have capital. And the folks with capital aren’t willing to share risk."