The Yellow River is named for the fine Loess soils from its headwaters, that are sandy colored and highly erosive. The soil dynamics of the river have created a fascinating but dangerous cycle; the river carries enormous amounts of sediment eroded from the surrounding plateau, and as this sediment-laden water flows, it gradually deposits material along the riverbed and banks, causing them to build up higher and higher over time - a process called aggradation.

Historically this natural buildup has forced Chinese communities along the river to continuously raise and strengthen their levees to contain the elevated riverbed. Over centuries, this process resulted in the remarkable phenomenon of a "hanging river" - where the river actually flowed at a higher elevation than the surrounding countryside.

While the levee system helped control regular flooding, it created the potential for catastrophic disaster. When levees failed, the elevated river would release with devastating force onto the lower plains, causing massive floods that were far more destructive than natural overflow would have been. The 1887 flood was a tragic example - levee breaches led to flooding across 50,000 square miles of land, nearly a million immediate deaths, and widespread starvation from crop failure.

This pattern of the Yellow River — of people constantly monitoring, building and maintaining levees and dikes, trying to control nature and control a river to stave off disaster—led to far greater disasters than would have occurred naturally. I start with this anecdote because it’s part of an old pattern, one in which our attempts to stave off relatively small negative effects leads to enormous negative effects. It’s not well understood, but the problems of agriculture today are the same as they have been for 6000 years. Despite massive improvements in technology, in our ability to understand and manipulate the growing of food, and despite massive gains in yields, we are still playing out very old patterns in the intersection of food, nature, and civilization.

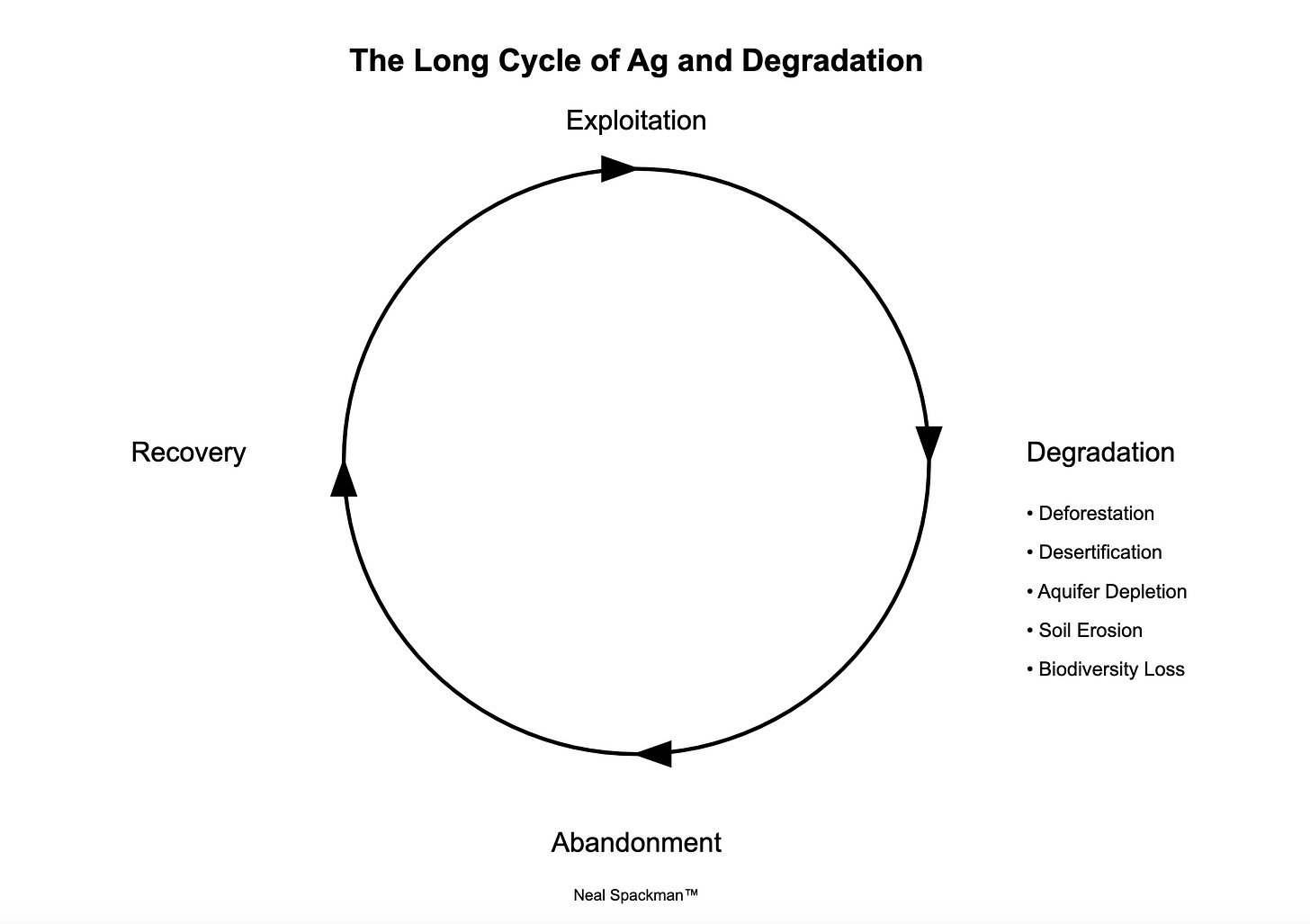

The cycle above is nearly-universal. People exploit nature for agriculture, which degrades ecosystems, leading to the loss of ecosystem services, which leads to collapse and abandonment. Sometimes that abandonment leads to recovery, and the cycle can start over again. Sometimes that abandonment doesn’t lead to recovery, but to a permanent state of degradation, and what ecologists would call a lower-energy stable state. How does this cycle play out?

The foundational resources of agriculture, and of human civilization, are soil and water. Soil and water are a result of mineral and water cycles, with carbon, nitrogen, phosphorous, and other minerals cycling through life in mycellia, in soils, in plants, in animals, and back again. This cycle is what keeps all living things alive — the carbon making up the atoms of our bodies, the nutrients and minerals that soils, plants, and animals need for health. And it is driven by the repeated birth and death of mycellia, and trillions of microbes in the soil. Soil is a living thing but we tend to treat it like dirt! Water, in a similar manner, cycles through all life, but also through the atmosphere and through soils and through strata underground.

These cycles, foundational to all terrestrial life, are maintained by ecosystems, which in turn are maintained by biodiversity. This is not merely tautological, but critical to understanding the long-term relationships between human societies, food, and nature. Soil and water underpin all human civilization, and biodiversity underpins all soil and water resources, through the maintenance of ecosystems and ecosystem services. Thus, all human societies are built on a foundation of soil, water, and biodiversity.

Despite all our accomplishment, we owe our existence to a six inch layer of topsoil and the fact that it rains.

Paul Harvey, 1978

Here is the rub: the way we produce food relies entirely upon soil, water, and biodiversity, and the way we produce food destroys soil, water, and biodiversity. Thus, the vast majority of agriculture systems are, in the long run, suicidal in nature. This pattern goes back to the earliest agricultures on earth, has played out on every continent (except Antarctica), in every biome, and is still repeating itself today. It’s a long cycle—often taking hundreds of years to play out—but it happens slowly, slowly, and then all at once. I could write at length on historical examples of this cycle playing out and how different geographies reacted differently, but i’ll keep them brief.

In the Euphrates and Tigris, the earliest irrigation known to man caused soils to degrade over time. Water from the rivers flood-irrigated newly-domesticated wheat fields. Each time irrigation was applied, a little bit of that water evaporated, and the trace salts in the water collected in the soil. Over time the soils became progressively more salty, so much that wheat harvests failed, and the crop was replaced by barley (which can handle more salt). At the same time, increasing population created demand for more food, while food production began to fall—creating a perilous inflection point that would exacerbate any other type of instability, political, military, or otherwise. This occurred in the late Akkadian Period (about 2200 BC), and again in the old Babylonian period (about 1600 BC). The irony and the wonder of all this is that these Euphrates civilizations — the first to develop an alphabet, written language, specialization, and other hallmarks of modern civilization— were both enabled by irrigation, and in significant part brought down by irrigation.

That’s not to say any of this is monocausal. Life is too complex to be able to say “this is the thing, all the time, every time.” But the degradation cycle of agriculture is never positive; it’s a threat multiplier, and an instability multiplier. It also gets reflected in different ways and reacted to in different ways. The Late Akkadian collapse led to some city states actually shrinking in population, as well as some migration out—people moved to other areas, abandoning land that was no longer productive. The Romans responded very differently.

When the Romans primarily inhabited Italy, wood was the main source of energy and a critical resource for ship-building. Deforesting hillsides in Italy allowed them to expand agriculture, and to harvest wood, but this led to enormous amounts of soil erosion, compromising productivity and leading to drought/flood cycles. Many agricultural areas became swamps—leading to the dual problam of a growing proletariat and falling agricultural productivity. Unlike the early Euphrates civs, the Romans didn’t abandon the land and move on—they went aconquering. Soil erosion and compromised agricultures contributed greatly to Rome’s military expansionism, as conquering decreased the number of mouths to feed while providing the empire with new agricultural lands. A fundamental problem was they never changed their agriculture though! So they degraded everywhere they went, and this was aptly noted in GT Wrench’s Reconstruction by Way of the Soil.

'Province after province was turned by Rome into a desert,' wrote Simkhovitch, 'for Rome's exactions naturally compelled greater exploitation of the conquered soil and its more rapid exhaustion. Province after province was conquered by Rome to feed the growing proletariat with its corn and to enrich the prosperous with its loot. The devastation of war abroad and at home helped the process along. The only exception to the rule of spoliation and exhaustion was Egypt, because of the overflow of the Nile. For this reason Egypt played a unique role in the empire. It was the emperor's personal possession, and neither senators nor knights could visit it without special permission, for even a small force, as Tacitus stated, might "block up the plentiful corn country and reduce all Italy to submission"

Latium, Campania, Sardinia, Sicily, Spain, Northern Africa, as Roman granaries, were successively reduced to exhaustion. Abandoned land in Latium and Campania turned into swamps, and Northern Africa into desert. The forest-clad hills were denuded. 'The decline of the Roman Empire is a story of deforestation, soil exhaustion and erosion,' wrote Mr. G. V. Jacks in The Rape of the Earth. 'From Spain to Palestine there are no forests left on the Mediterranean littoral, the region is pronouncedly arid instead of having the mild humid character of forest-clad land, and most of its former bounteously rich top-soil is lying at the bottom of the sea.'

Note that the Italian regions that Rome exhausted recovered ecosystem function as wetlands, but North Africa has never since recovered the forests, wetlands, and agricultural productivity that existed prior to Roman colonization and exploitation. Deforestation led to drought/flood cycles and desertification, such that natural rehabilitation and recovery will never happen without human-driven terraformation (by the way if there are any N. African or ADB leaders reading this, I can design and lead that for you).

There are other such examples — old ones on the Indus, or the Maya in Mesoamerica—and much more recent examples as well. The destruction of the Aral Sea by soviet cotton schemes, the dust bowls of mid 20th century America, the collapse of rice farming in W. Africa in the 20th and 21st centuries —all variations on a theme in which agriculture replaces ecosystems, messes up the water and mineral cycles, degrades soils, and thus its own foundation, and eventually collapses.

And this is the terror of modern agriculture: this same cycle is happening nearly everywhere today. Deforestation, desertification, soil loss, dead zones in our oceans, fishery collapse, and biodiversity loss all compromise future generations’ ability to produce food. Just as with the Romans, we have grown our population through a marvelous and advanced food system, in such a way that this food system cannot persist and will inevitably degrade its own resource base.

Here is how these patterns tend to play out:

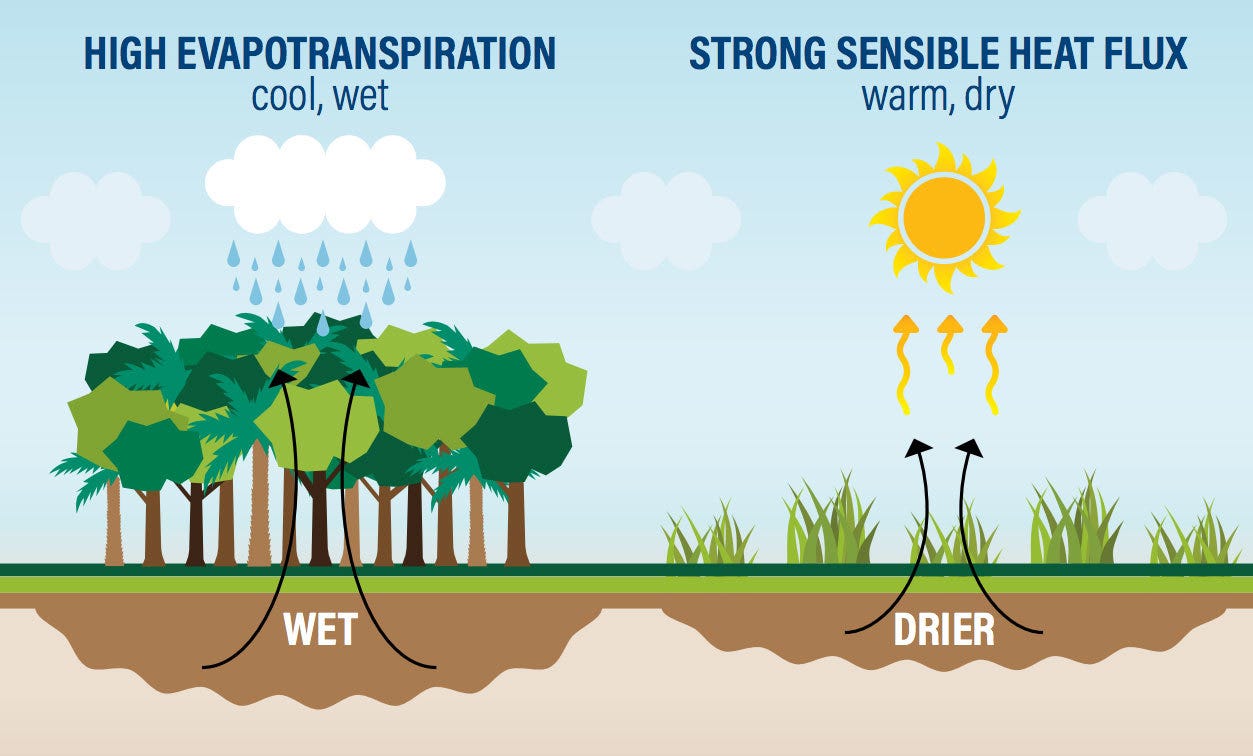

Deforestation leads to massive soil loss and changes the small water cycle, leading to drought-flood patterns in which rain is no longer reliable, and when it does come it comes in destructive flash-floods. This is because the foliage and ecosystems that manages water, slows it down, and puts it in the soil, are replaced by annual crops. Higher temperatures, drier soils, and less capacity to both induce rain and retain water in the land all contribute to a heating, drying, soil-eroding pattern.

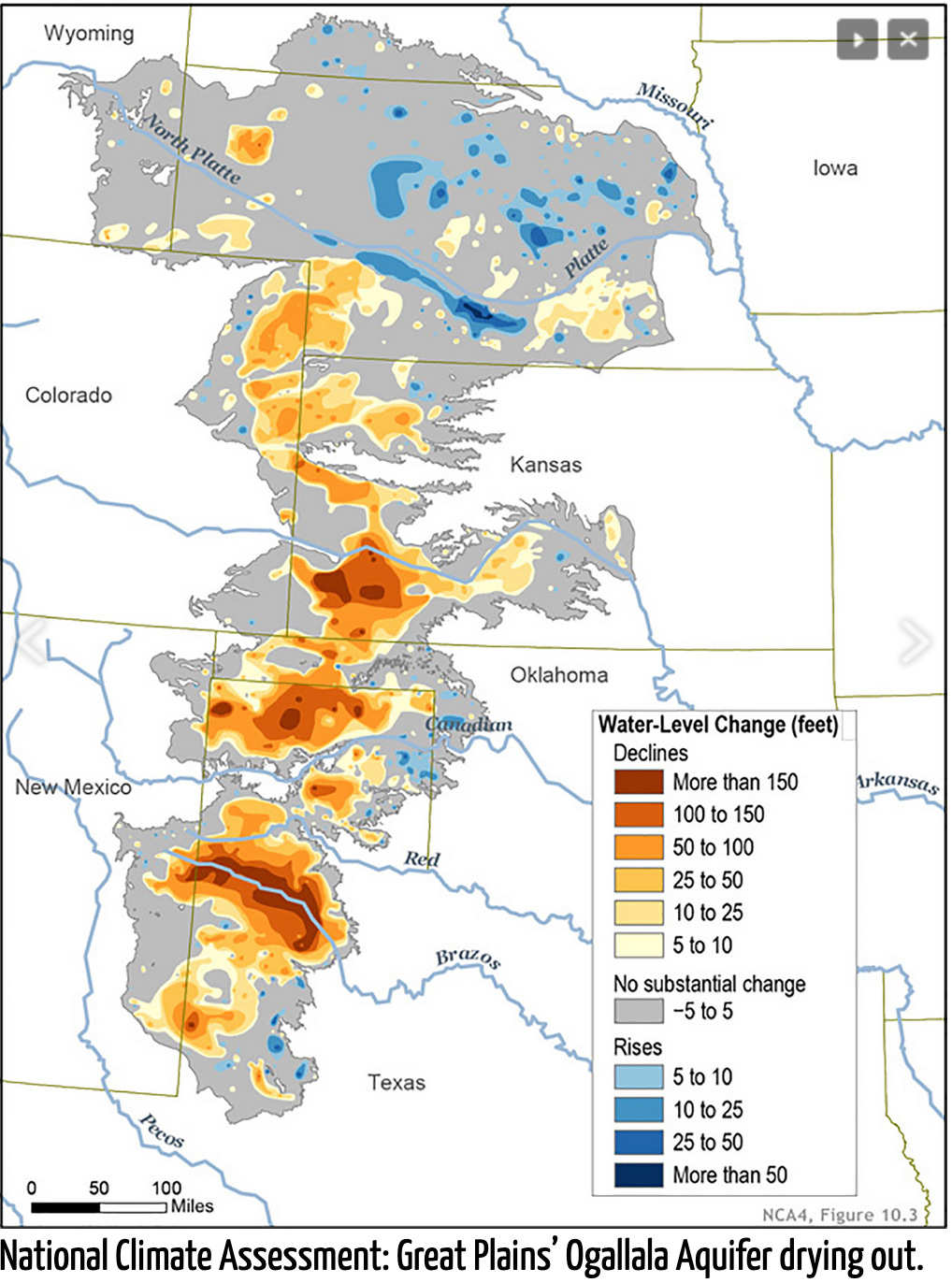

Plowing and Irrigation further soil erosion, eliminate the soil’s ability to absorb water, and lead to greater disruption of water cycles, leading to aquifer depletion and worsening flood dynamics. The average soil loss in the US Grain belt is 1.9mm per year. With a starting depth of 80-150 cm, that means after some 200 years of continuous farming, in some areas soil will be completely gone. This has already happened, as according to multiple studies, 1/3 of the US grain belt is now devoid of topsoil.

Heavy fertilization leads to riparian degradation and dead zones in waterways. Today the largest dead zone in the world is in the Gulf of Oman, caused by fertilizer runoff from the Indus river. Pakistan heavily subsidizes nitrogen fertilizer, and overfertilization of farmland along the Indus leads to massive nitrogen overload in the gulf. The miracle of self-sufficiency in Pakistan is blunted by the fact that it has the largest micronutrient deficiency in the world, and has caused the largest dead zone on the planet—amounting to billions of dollars in damages every year in lost -fishery productivity and lost biodiversity.

The dead zone in the Mississippi Delta in the USA causes an estimated 2.4 billion in damages every year, according to the Union of Concerned Scientists. 90% of this damage is driven by runoff from agricultural lands, and 10% from municipal runoff. Does it make sense to push agricultural productivity as high as possible, when it kills off entire fishery industries? The oystermen, shrimpers, and fishermen get the shaft, just so every farmer can squeeze out another few bushels?

Biodiversity extinction is happening at an accelerated rate: between 1,000 and 10,000X faster than should be expected, according to the WWF. This is primarily driven by agriculture — the widespread use and increase of biocides, the widespread deforestation of forests, plowing of grasslands and savannahs, and overharvesting of fisheries. Remember—soil and water are maintained by ecosystems, which function via biodiversity. Without biodiversity, we don’t get ecosystem function, and without ecosystem function, our soil and water resources are eroded, and eventually depleted. Human society cannot survive without biodiversity, soil, and water.

Thus, whether we are talking about soil, water, ecosystems, or oceans, today’s dominant food systems are inherently suicidal and autodestructive, compromising the foundational resources that future generations will need to produce food. This is the terror of modern ag: it feeds us and enables a massive population, at massive long-term cost.

The Nation That Destroys Its Soil Destroys Itself

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Like the Yellow River anecdote at the beginning of this article, we are building up to a massive disaster, in pursuit of preventing smaller ones. It is axiomatic that something that cannot go on forever must inevitably come to an end. We cannot deforest, denude, desertify, and degrade land indefinitely. In trying to feed a growing population, we are like the Chinese building up the dikes on the yellow river, trying to prevent a disaster, and inadvertently creating the conditions for the worst disaster ever. Nature always bats last. The catastrophe that will come, if we do not redirect our creativity and ingenuity to developing non-suicidal food systems, is inevitable, as we continue to degrade the foundations of all human societies: soil, water, and biodiversity.

Great encapsulation, clear and concise. It could use a third part--what to do about it. I realize that's not a simple matter, but parts one and two kind of lead in that direction. And given your particular expertise, it would be interesting to hear your take.

Brilliant article. Thank you. Sadly even though there are solutions and different ways to farm, it would be the difficult path, and not involve much money making so there is not too much hope really